Kowtowing to Erdoğan From France, NATO, and Europe - They Will Put the Turkish Grey Wolf to Guard the Sheep

Multinational security system and border changes in the Ukrainian and Cypriot issues

· How is Turkey gaining ground at the expense of Cyprus and Greece?

· What can Nicosia and Athens do?

Turkey has once again managed to be at the center of international attention, particularly on the Ukrainian issue, with Europe—and especially France—ready to upgrade it strategically, in a display of diplomatic obeisance, while Ankara itself lays down conditions. Specifically: if Turkey is to participate in any peace process—in other words, if it is to send troops—it insists on: (1) having control, and (2) linking that control to the exclusion of countries that were not neutral in the Ukraine war.

This position is very close to Moscow’s and effectively works as a diplomatic blackmail of the Europeans. Why? Because Russia has made it clear that it will not accept European or NATO forces on Ukrainian soil. That rules out France, the UK, Germany, Poland, etc. Turkey seizes this position and argues that since these NATO countries do not belong to the neutral camp, only Turkey could participate in a multinational force, since, by its own claim, it was not hostile to either side. Just as in World War II, it poses as the “cunning neutral” who expects and demands benefits.

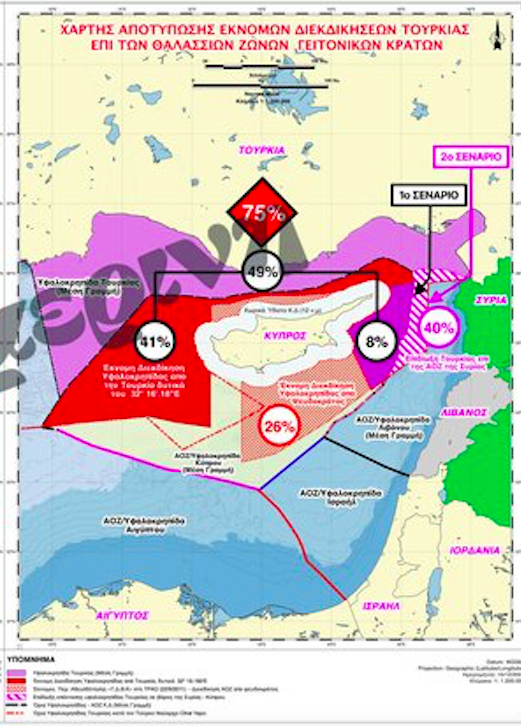

The Blue Homeland and the "Aegean Sandwich"

Under these circumstances:

First, France, through Macron, stresses that Turkey should be invited to take part in the security system in Ukraine—which, however, is tied to the broader European framework, what is being called the new security architecture.

What does Macron’s invitation mean?

- For the formation of a multinational force, around 100,000 troops on the ground would be needed.

- The U.S. has said it will not send troops.

- It is not certain which other EU countries are willing to participate.

Therefore, Turkey is seen as necessary. But leveraging this need, Erdoğan demands a leadership role and the exclusion of the rest of the Europeans—just as Russia does. That would mean Turkey, alongside other “neutral” states like India or others, would dominate the game, making the deterrence of any new Russian threat dependent on him. De facto, this would give him a central role in the new European security and defense architecture.

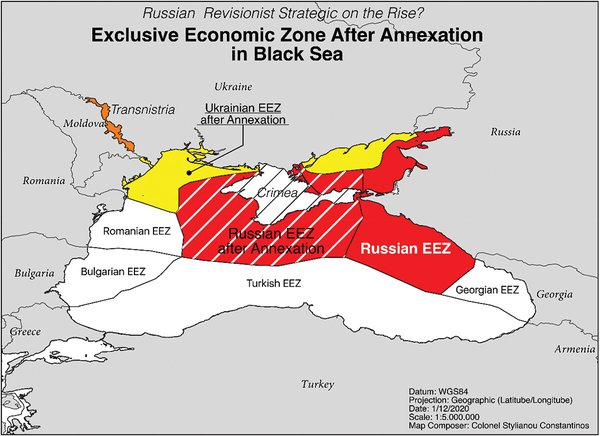

Already, France argues that since Turkey shares maritime borders with both Russia and Ukraine, its fleet—as a NATO force—has a role to play in the Black Sea. This is a point also discussed in NATO. Moreover, the Bosporus and the Dardanelles are of vital importance for Western security, as well as for trade and navigation.

Some key points here: a) Since Crimea is considered lost for Ukraine, there is a new EEZ, largely shared between Turkey and Russia. b) Ankara legitimizes its role in the Black Sea under the concept of the “Blue Homeland,” via NATO and the EU. c) If Turkey consolidates its position from the Black Sea down to the Dardanelles and in the Eastern Mediterranean (thanks to Greek absence), it will strengthen its claims in the Aegean. Increasingly, the Aegean risks resembling a Turkish “sandwich.” This especially applies with Ankara seeking to control the Aegean’s gateways—from Crete, Karpathos, Rhodes in the south to the Dardanelles in the north.

ΔΙΑΒΑΣΤΕ το άρθρο στα ελληνικά - Τεμενάδες στον Ερντογάν από Γαλλία, ΝΑΤΟ και Ευρώπη

The Peacemaker…

Second, Turkey now plays the role of peace-broker. And it will participate with military forces in a system of guarantees. If it participates in Ukraine, why not also in Cyprus? How do Russians, Europeans, Americans, and Ukrainians see Turkey? As an invader, or as a peacemaker? The answer, of course, is the latter. And that happens for two reasons: first, because it suits their interests; and second, because Turkey continually receives a blank check from Athens and Nicosia. No official statement has been made by Greece or Cyprus along the following lines: How can Turkey be accepted as a peacemaker in Ukraine while it occupies territory of the Republic of Cyprus, an EU member state?

Upgrading and Border Changes

Therefore, what is happening in Ukraine is directly connected to the Cyprus issue on several levels:

- Turkey’s geopolitical and strategic upgrade within Europe, tied to the new security architecture—linked not only to Ukraine and containing Russia, but also to industries, particularly the defense sector, both inside and outside “safe” borders. Under these conditions, Turkey’s voice within the EU is strengthened, regardless of whether it is a full member or not. Will the EU be vulnerable and dependent on Ankara? Who will pressure whom—the EU on Turkey, or Turkey on Brussels?

- What will the position of the Republic of Cyprus be regarding border changes? This issue has legal, political, geopolitical, and diplomatic dimensions.

Under international law, border changes or annexations by force are not permitted. This is confirmed by:

- Article 2, paragraph 4 of the UN Charter,

- The 1975 Helsinki Final Act on the inviolability of borders, and

- Article 4 of the EU Treaty, which respects the territorial integrity of its member states and explicitly forbids sending troops into the territory of a member state.

The only legitimate case of border change is a peaceful agreement between the parties—even if that comes after a war. Examples include:

- The “velvet divorce” of Czechoslovakia,

- The post–WWII Polish-German border settlement,

- Yugoslavia’s breakup (Slovenia and Montenegro leaving peacefully, Croatia, Bosnia, and Kosovo through war—the latter still unresolved legally).

Kosovo, Cyprus, Crimea

Kosovo is particularly instructive, because: A) The Republic of Cyprus, Greece, and Spain refused to recognize it, for obvious reasons—so it would not be used as a precedent for the Basques, Catalonia, Thrace, or occupied Cyprus. B) Russia invokes it as follows: How can Europeans and the U.S. recognize Kosovo—an autonomous province of Serbia—but not recognize Crimea’s annexation, which came through a referendum, invoking the right of self-determination? Moscow extends this argument to the four regions it now controls in Ukraine (Donetsk, Luhansk, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia).

Sovereignty and Guarantees

It must be made clear from now that no Ukrainian model can be applied to the Cyprus issue, because:

First, we do not consent to border changes. By definition, the logic of two states or annexation is rejected, since our consent would never be given—as might happen in Ukraine. Here arises the question of a disguised border change: that of a federation with confederal characteristics, which would: A) strip Greek Cypriots in the north of their right to vote, B) grant rights of primary law—such as residual powers to the constituent states—meaning that

any powers not explicitly assigned to the central authority would belong to the constituent states as separate sovereign rights, C) fail to specify explicitly that sovereignty derives from one people and one source of authority—instead, as per the Anastasiades–Eroglu agreements, it would state that sovereignty derives equally from Greek Cypriots and Turkish Cypriots.

Even these three points alone would be used by Turkey to press for separate sovereignty and a change of borders through federation, but this time with our consent.

Because, moreover: i) Today, the lawful residents of the north are the refugees and their descendants. But the day after a federation, virtually no Greek Cypriot would remain there with voting rights, since the convergences already stipulate that they would not have the franchise—ensuring that the north remains permanently Turkish in demographic and administrative terms. The status of Greek Cypriots in the north would be akin to what they have today in Germany or the Netherlands: residents without a vote. And the right to vote is inherently tied to the homeland, the state, and the borders. Thus, the administrative borders would, in practice, become state borders. ii) In Kosovo, eastern Ukraine, and especially in Crimea, the majority population was ethnically Russian—native to the region. By contrast, in the northern part of Cyprus, the lawful and indigenous residents are not Turkish Cypriots nor settlers, but overwhelmingly (over 82%) Greek Cypriots. This concerns not only the population but also land ownership.

Second, the system of guarantees—if properly applied in Ukraine—would concern the country’s security. In Cyprus, however, the system of guarantees was the pretext and cause of invasion and occupation. The invader and occupier, i.e., Turkey, cannot simultaneously be a guarantor in Cyprus. It is a grave mistake that we have not raised the issue that such a country should not be allowed to participate in comparable missions, since it already violates both international and EU law.

On this point, Athens and Nicosia should have raised the matter within the EU—even as a form of pressure—by stressing that Turkey can only send troops to Ukraine and take part in any effort of the new security and defense architecture if: A) it begins withdrawing its troops from Cyprus, based on a timetable, and B) not only do we reject any border changes, but we also emphasize that the constitutional solution must mean the continuity of the Republic of Cyprus and the reintegration of Turkish Cypriots into it, with full respect for EU principles—from freedom of settlement to property rights and voting rights. In other words, we will not go as “tourists” to the north.

The “Cowboy’s” Intervention…

All the above must be clearly conveyed to the United States. Because if President Trump gets involved in the Cyprus issue—in his own “cowboy” style—he will not hesitate, cold-bloodedly, to redraw the borders in Cyprus and the Aegean, following the model of the Black Sea and Ukraine.