Turkish Advance and the Erosion of the Buffer Zone

Occupies 3.76% of the free areas after 1974, and with the buffer zone included, reaches 7.7%

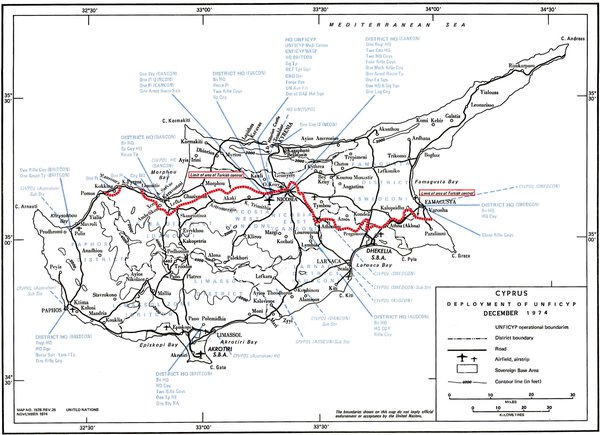

Since 1974, Turkey has continued to push forward, gradually eroding the buffer zone. With UNFICYP’s tolerance, this process has created ongoing problems for the National Guard and in areas where arable land lies inside the buffer zone. What follows are maps and facts that reveal another dimension of the Cyprus problem, directly tied to the territorial issue, if and when a final settlement is negotiated.

The United Nations and the Cypriot Governments

The UN’s role in Cyprus has never been what it should. In many cases it has not even been neutral. It often appears pro-Turkish, since by claiming to keep “equal distance” it in fact applies the rules of the strong rather than those of the UN Charter. Responsibility, however, also lies with successive Cypriot governments, which have accepted one fait accompli after another. The result has been the steady advance of the Turkish occupation forces from the ceasefire of 16 August 1974, 18:00 hours, until today.

That advance, amounting to an expansion of the occupation and covering parts of the buffer zone, is 234.77 sq. km or 3.94% of the free areas of the Republic of Cyprus. Specifically: after 16 August 1974 the Turks took an additional 3.76% of free areas, while the buffer zone—wrongly defined—extends to 3.94%. This figure is misleading, since the UN included in the buffer zone areas that were never occupied or disputed, but have always been part of the free areas. Examples include Athienou, Deneia, Mammari, Troulloi, Pyla, and the Nicosia International Airport area. Many of these contain Greek Cypriot farmland, which explains the recurring disputes with the occupying forces and UNFICYP over cultivation rights and boundaries.

ΔΙΑΒΑΣΤΕ ΤΟ ΑΡΘΡΟ ΣΤΑ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΚΑ - Τουρκική προέλαση και ροκάνισμα «νεκρής ζώνης»

How the Situation Was Created

The ceasefire agreement of 16 August 1974 gave UNFICYP the task of recording the ceasefire line. The first map, in the Secretary-General’s December 1974 report, showed only the Limit of

Area of Turkish Control, with no buffer zone. A second map in June 1975 was similar. But a third, in December 1975, arbitrarily included a trace of the National Guard’s line and defined the space between the two as a buffer zone. At the same time, it changed the terminology: the Attila line was called the “Forward Defence Line of Turkish Forces,” and that of the National Guard the “Forward Defence Line of Cyprus National Guard.” The notion of “occupation forces” disappeared.

Later reports spoke instead of “Ceasefire Lines of Turkish Forces” and “Ceasefire Lines of Cyprus National Guard.” In this way, the original 16 August 1974 ceasefire line was altered, reflecting ongoing Turkish advances, with serious political and military implications.

The last such map was in the Annan Plan, which adopted the Turkish view of territorial boundaries: not what Turkey held at 18:00 on 16 August 1974, but what it had pushed forward to later. Since then, advances have been recorded at various stages—1975, 1976, 1978, 1988—extending to Strovilia, Pyla, Agios Dometios, and elsewhere. The result has been not only an advance of occupation forces but also erosion of the buffer zone, which is in fact part of the Republic of Cyprus.

Sovereignty and the Buffer Zone

The buffer zone is not occupied territory. It lies beyond the Attila line, and sovereignty belongs to the Republic of Cyprus. UNFICYP operates there under arrangements with the lawful Government and the UN Security Council, based on Resolution 186 of March 1964, which recognized the Government and the Republic of Cyprus as the sole legitimate authority.

This is precisely the resolution the Turkish side wishes to cancel by means of a separate agreement with UNFICYP, seeking a form of recognition through the Security Council. The occupied areas, however, remain an inseparable part of the Republic of Cyprus, though effective control cannot be exercised due to the illegal presence of Turkish troops—who bear full responsibility for what happens there. This is confirmed by Protocol 10 of Cyprus’s EU accession, and by rulings of the European Court of Human Rights (Fourth Interstate Case and Loizidou v. Turkey), which describe the pseudo-state as a puppet controlled by the Turkish army.

The Problem of Different Maps

The buffer zone has been arbitrarily defined by UNFICYP, and successive Cypriot governments have tacitly accepted it. As a result, Turkish advances have been consolidated, and contradictory maps now exist: the National Guard and Defence Ministry use one set, while the UN and Foreign Ministry rely on another.

In Athienou, for example, UN officials considered it a violation of the status quo when National Guard vehicles drove through the town to resupply outposts. Thus, even routine logistics depended on whether the National Guard’s Chief was willing to challenge UNFICYP’s interpretation. Similar issues arose at Nicosia airport and elsewhere.

What recently happened in Pyla is not an isolated case. Strovilia saw three such incidents before: in 2000, 2003, and 2019, when three houses were taken under control and residents were told they were “citizens” of the pseudo-state.

Main Problems

The conflicting maps and boundaries cause multiple problems:

- Turkey claims the buffer zone is not neutral ground but occupied territory belonging to it.

- Greek Cypriot properties are wrongly included in the buffer zone.

- National Guard positions and supply routes are affected, creating operational issues.

The Territorial Question in Negotiations

All this leads back to the key issue: territory. On the basis of which maps have negotiations been held? Where is the true ceasefire line, and where are the buffer zone’s limits? What percentage of land would actually be returned in a settlement, and under what conditions?

Both during the Annan Plan and today, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs relies on UN maps—arbitrary, essentially aligned with Turkish positions, and accepted without objection by the Cypriot side. The expansion of occupation is 3.76%, while the buffer zone as defined by UNFICYP is 3.94%—a total of 7.7%.

Turkey considers this land its own, and any return of part of it would be presented as a “concession,” in exchange for recognition of separate sovereign rights. Turkey’s position is clear. The question is: aside from failed PR maneuvers, what is our own side’s substantive response?

Caption 1: This map shows, in red, the Turkish advance since 16 August 1974, and in yellow, the buffer zone as arbitrarily defined by the UN Peacekeeping Force.

Caption 2: Both maps are UN-issued. The first, December 1974, shows the ceasefire line and the Turkish advance. The second, December 1975, shows the Attila line (in red) and, arbitrarily, the National Guard line (in blue).